How Burnout Made Me Recognize the Gaps in the Model Minority Myth

…and how I was unknowingly holding myself to it.

Photo (2018) courtesy Kimberley Wong.

In the evenings, when I’m pondering my existence and sharing the couch with my cat, looking out the window at the traffic zooming by our second-floor apartment, I listen for the rustle of keys that signifies my roommate has come home after their long day of working a double shift.

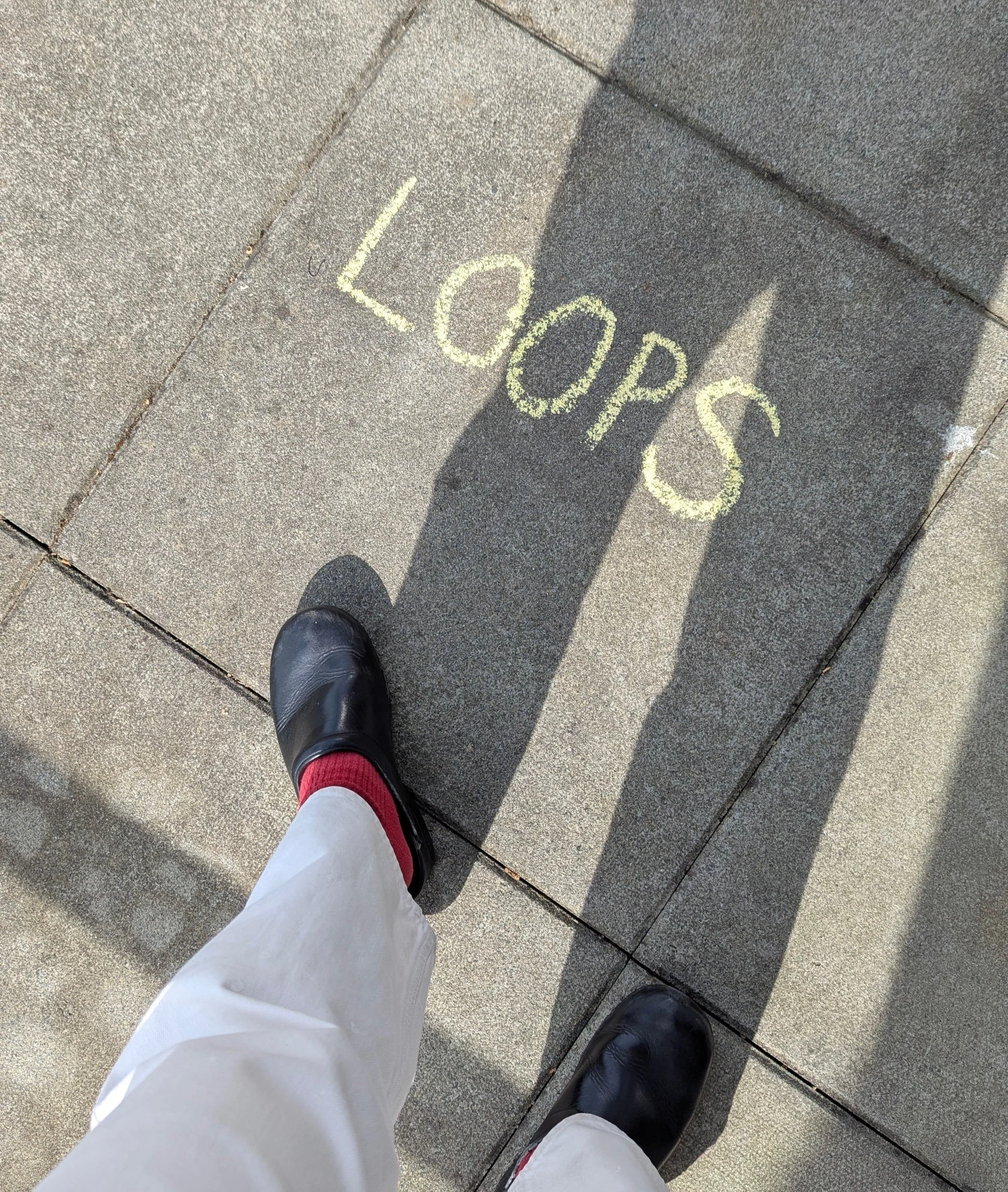

They usually wash their hands, grab something to sip, join me on the couch and have just enough energy to mutter the word “loops.” We usually laugh hysterically at this for a minute or so, then catch each other up on our days.

I think about this word, “loops,” in the context of my current life a lot. It was a couple of years ago when I decided to remove myself completely from what I believed was the source of my burnout—to remove myself from the “loop.” I stopped seeing most of my extended family because I was viewed by them as the queer-socialist-outcast-cousin brooding in the corner of every family get-together (and they were correct). I stopped volunteering on community non-profit boards, stepped down as co-chair of a municipal advisory group and left messages on read for opportunities to do media interviews. I ghosted friends that didn’t reciprocate the care and energy that I gave to them. I isolated myself, protected my peace and started on my journey of healing. Around that time, I would see the word “loops” drawn in chalk on the sidewalk around my city. It felt like something was trying to tell me that I was on the right track, stopping the “loops,”—the cycles of trauma—from restarting.

Photo (2019) courtesy Kimberley Wong

I started myself on this loop of burnout because I used to think that every opportunity to participate in spaces of power was a door to a more bountiful life, a more successful career and a happier future self. I would take on responsibilities like it was my job—fulfilling the role of eldest daughter everywhere I found myself. I was a filial piety superstar to every organization I served.

I thought I was seeking liberation and purpose in my servitude, but behind all this was the monster of the model minority myth. I was unknowingly picking up where my parents left off. They had both come from humble beginnings—restaurant workers, large families with lots of mouths to feed and limited resources. And now, they’re both professionals who have had successful careers in finance. Though their career paths are a common reaction to growing up in households where money was posed as freedom, and where there often wasn’t enough of it to gather more than basic necessities, I now realize that this is also a reaction to their parents’ traumas from escaping dictatorial governments and hoping for better lives in their new country.

“I thought I was seeking liberation and purpose in my servitude, but behind all this was the monster of the model minority myth.”

Their parents suffered under the wrath of men who sought total and unquenchable thirst for control and power over the people they led. My grandparents, rightfully, feel apathy and distrust in governments, and passed on generational political avoidance and inaction because of their experiences and feelings of powerlessness. I observed my parents’ role in society, and would follow suit by picking up the pieces, hoping that I would fit into the same mould as them—putting our heads down and working hard, staying silent to the injustices around us. But I was never able to.

Photo (2011) courtesy Kimberley Wong

I tried to be so many different things for so many different people, with the weight and responsibility of representing my community and my identities in every space that I was in. From pushing my family to question their political belief system and apathy in government, to being tokenized as the only person of colour in political organizing spaces, I fell through the cracks of the model minority myth and the limits I was conditioned to believe were set.

When I reached the bottom of the hole, I could identify the loops: generational trauma within my family, patterns of abuse of power in the leaders of the organizations I was serving and my own nervous system spiralling into chaos and doom from trying to keep up with this all. And I saw how the model minority myth made stories of struggle, resistance and resilience like mine invisible. It rewards people like my parents who are less threatening to white supremacy—those with lighter skin, those who can speak unaccented English, who can excel in demanding hyper-capitalist environments, those with the social mobility to assimilate. But reaping the rewards of the model minority myth doesn’t break down systemic barriers, it leaves those who do not so easily fit into the model minority myth to fall through the cracks of the system and reinforces inequities.

“Reaping the rewards of the model minority myth doesn’t break down systemic barriers, it leaves those who do not so easily fit into the model minority myth to fall through the cracks of the system and reinforces inequities. ”

Sometimes, falling through the cracks looks like and results in burnout—that was my body’s reaction to trying to fulfill the impossible.

But the qualities the model minority myth deems unfavourable are so often invisible to those who don’t experience them, like neurodivergence, queerness, transness. So I ask, as we become more accepting of the diversities within our own Asian diaspora, can we also pay attention to the ways in which the model minority myth is used to pit those who fit into those rigid definitions of acceptability against those who never will? They deserve equity and care nonetheless.

Removing myself and ending the “loops” was a necessity that my body demanded of me. And even so, recently, I’ve been saying to myself, “we owe each other a lot.” As in we, the Asian diaspora, owe each other a lot. We share similar histories of vast, difficult migrations across oceans. We’ve all witnessed the sacrifices that our parents have made to give us a better life. We worry about their aching joints, witness their hands aging and see the growing number of freckles strewn across their faces. Our love and commitment for our people, culture and community is complicated but boundless. And we can imagine a world beyond the limits of oppressors, colonizers and bullies. If not for us, then for them.

Photo (2024) courtesy Kimberley Wong

Something within me yearns to think about the life I could be living if I hadn’t been caught within the loops of the trap that is the model minority myth.

What relationships could we hold with one another if we acknowledged our shared humanity? If we weren’t held to the impossible standards of the model minority myth? What would our communities feel like if we sat with one another in discomfort, questioning the power of our oppressors instead of seeking their validation? What are the difficult conversations about our past and future we have been avoiding?

The time I spent in isolation helped me come to the realization that many of the issues we face as a generation and species rely on our ability to heal collective traumas together. Because I needed my roommate to remind me of the relentlessness of her “loops” while I had the privilege of dismantling mine. That I couldn’t process all of this alone, or heal in the way that capitalism makes us believe is the only way to do it—with bubble baths, retail therapy or being a participant in stolen, misrepresented practices of white people teaching their version of holistic eastern medicine. Cycles of oppression and supremacy will reign unless we start on journeys of healing together—harnessing our anger to remind us that we deserve to break out of these cycles of oppression, generational trauma and burnout.

Interested in learning more? Reorienting Our Trauma: A Workbook for the Asian Diaspora is a publication that grew out of a weekly group therapy program by the same name, hosted by the local non-profit hua foundation. It was started with the intention of providing space for the Asian diaspora to speak up about the struggles and injustices we face collectively. The Workbook features a mix of activities, holds space for reflection, and shares the language one can use to name, cope with, and rewrite our trauma. Get a free copy at bit.ly/trauma-workbook.